Three Men And A Dream

One day when they were in South Africa shooting a movie together, Matt Damon and Clint Eastwood went out for a beer. Several months later, Damon jokes about the evening.

“I’m not sure if you remember,” he says, flashing a broad smile at Eastwood, “but you leaned over and told me, ‘You know, I really do know what I’m doing.’”

“It’s pretty sad I had to explain that,” Eastwood says, with a slight twinkle in his eye.

“No, no, believe me, I knew it!” Damon replies.

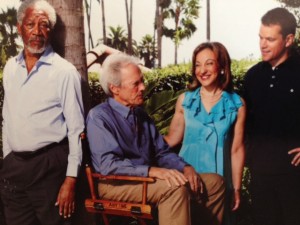

The two have reunited on this sunny day along with actor Morgan Freeman to talk about the movieInvictus (opening Dec. 11) that has come to feel very personal to all of them.

Set in South Africa in the mid-1990s, the film spins a complicated political situation into a profoundly moving and very human story. Nelson Mandela spent 27 years in prison for opposing apartheid. After he was released and elected as South Africa’s first black president, he preached reconciliation. When he decided to support the country’s rugby team—long a symbol of white oppression—his countrymen were stunned. “Forgiveness liberates the soul,” Mandela explains to a crowd. “That’s why it’s such a powerful weapon.”

Freeman gives an astonishing, note-perfect performance as Mandela. Eastwood directs the movie, and Damon portrays the captain of the rugby team, who comes to understand that the Rugby World Cup isn’t just a tournament—it’s a chance to unite the country.

The day we all meet, the three stars sit together comfortably at a hotel in Los Angeles, far from the strife of South Africa. Damon sips a cappuccino, Eastwood nibbles some fruit, and Freeman nurses the arm that is still weak after a car accident a year ago. Despite Oscars, adulation, and extraordinary amounts of money, no hint of ego bubbles in the room. They may be among the most-admired actors in the world, but in person they are easygoing, thoughtful, and down-to-earth. The respect they have for one another is apparent.

“It’s fun working with young Matt,” says Eastwood, 79, clearly the revered elder in the group. “He’s great and does a terrific job. I’d look at him often and think, ‘I wonder if I was that good when I was his age.’”

He pauses for a moment, reflective. “Chances are I wasn’t. But it was fun to be vicarious and think, ‘Yes, that’s a role I might have done.’”

Eastwood talks more softly than he used to, and his hearing isn’t as sharp. The tough-guy style of his earlier years has given way to a calm confidence. His brilliance as a director is to make entertaining movies that explore important subjects, from war (Flags of Our Fathers) to immigration (Gran Torino) to racism. On a movie set, he hasn’t lost a bit of his edge. He still works quickly and decisively. Other directors may shoot a scene a dozen or more times, hoping to get it right. Eastwood does it once or twice—and moves on.

“I work from the gut,” Eastwood admits. “You can tell any story 20 different ways. The trick is to pick one and go with it.”

Was he always so sure of himself? “Oh, I don’t think anybody begins that way—otherwise it feels like arrogance. The reason I still work at this stage of life is because I enjoy learning something new every day. When you accept that it’s a constant learning process, it’s fun.”

Damon nods. He shares Eastwood’s intelligence and instinctive desire to learn. At 39, “young Matt” looks 10 years younger, and he’s even handsomer than onscreen. His arms flex impressively under his T-shirt, and his eyes flash with wit and humor.

“I felt a lot of responsibility playing this role, and I came prepared, because I knew I’d have only one shot to get it right,” he says, teasing Eastwood.

Freeman, 72, says he felt totally comfortable giving voice to Mandela’s extraordinary lines.

“This may sound stupid, but as an actor you embody the role, and whatever you say is from total conviction,” he explains.

The actor first met Mandela in the early 1990s. “He told me he wanted me to play him in a movie someday,” Freeman recalls. “I said, ‘Then I need access to you, and I need to be able to hold your hand.’ And he said, ‘We’ll do that.’ So anytime we were anywhere in proximity after that, we’d shmooze.

“I’ve always been preparing for the time I stepped in front of the camera as him,” Freeman adds. “The luckiest part of my entire existence is finding this script and sending it to Clint, and then he said, ‘Yes.’”

“Morgan knew Mandela long before we did. When you meet Mandela, you think, ‘Oh, he’s doing Morgan Freeman,’” Eastwood says with a laugh. “Morgan has all his gestures and his throat-clearing.”

Freeman captures Mandela’s wisdom and strength—and his humanity. With a gesture or a glance, he reveals the gentle man behind the martyr.

“I’m not religious,” Eastwood says, “but it takes someone of superior morality to behave as he did. Christ said, ‘Forgive these people for they know not what they do.’ Mandela literally was doing the same thing.”

In the movie, Damon as the white (and very blond) rugby captain François Pienaar wonders to his wife, “how you spend 30 years in a tiny cell and come out ready to forgive the people who put you there.” Damon admits that the line resonated with him.

“It makes you consider your own place in the world and your behavior to other people,” he says. “It’s very emotional and very hard to understand.”

In South Africa, the stars visited some of the poorest townships. And they spent considerable time thinking about the seeds of racism.

Eastwood grew up in Oakland, Calif., where, he says, “There was a high population of black people. I went to a multiracial high school, but the other school in town was all black. I loved music, but I never could figure out, Why can’t black players play in a white band? Why can’t white players play in a black band?”

He shakes his head. “My wife’s part black, and she grew up in Fremont, California, with people saying ‘You can’t drink from that tap’ and calling her bad names. I like to think we’re way beyond that, but so much prejudice, even now, comes from parents. The old mentality that someone is superior to someone else is shoved down at the kids, and they carry it all their lives.”

Freeman recently made a documentary about a Mississippi town that continues to hold racially segregated proms. “On weekends, the black kids are on one part of town and the white kids are on another part. They’re not allowed to date or intermingle. When I heard about the proms, I asked, ‘Why?’ They said, ‘It’s not our idea. Our parents insist.’”

In addition to such blatant examples, Freeman worries that parents can pass along prejudice unwittingly. “Children don’t listen to what you say, they watch what you do. I’d use the analogy of a guy walking down the street with his daughter. He’s holding her hand, and a dog approaches. He says, ‘Don’t be afraid,’ but he squeezes her hand. What is the message?”

Now that he’s a father, Damon cares more than ever about encouraging tolerance. He and his wife, Luciana, are the parents of Isabella, 3, and Gia, 1, as well as Luciana’s daughter from a previous marriage, Alexia, 11.

“I don’t think it’s a natural state for children to be prejudiced,” he says. “A case in point: I was trying to explain segregation to my stepdaughter. We talked about Alabama in the ’60s, and she was utterly baffled. Alexia is very dark—her father is Cuban, and my wife’s Argentinean—so I tried to explain that she probably would not have been able to use white water fountains. She goes to school with all types of kids and plays with everyone, so it was a lot for her to grasp.”

Eastwood doesn’t let any of the characters in the movie lecture about racism. Instead, a rugby team becomes the prism for understanding. In the stands and on the streets, South Africans band together behind the Springboks—a team that blacks had previously reviled. People who’ve been resentful of one another form bonds, and Mandela’s belief in forgiveness comes to fruition.

And rugby may get new fans. The action on the field is nonstop, and the players are tough. “I worked out and did a lot of weight lifting,” Damon says. “I put on good muscle weight, but I could not for the life of me build up my legs enough. These guys have legs like tree trunks.”

Eastwood’s son Scott, 23, plays one of the rugby players. “He got smacked around a lot,” Eastwood says. “One day he was knocked down particularly hard, and once I saw he was okay, I said, ‘Oh, it’s good for him.’”

“It’s a young man’s game,” Damon says. “I definitely relied on my double more than I would have 10 years ago.”

Vanity doesn’t seem to play a role in any of the actors’ lives. All three men are serious, sharing a passion of purpose and an eagerness to discuss meaningful topics. But as soon as we finish our conversation, each will be heading off to his next project, including another film that teams Eastwood with Damon.

“None of you takes much time off,” I say.

“If you take time off, you get more off than you want,” Freeman says with a laugh.

“About 8 or 9 years ago, I went off with a couple of guys, and we made a movie for free in the desert,” Damon says. “It didn’t have any story—we improvised the whole thing for fun. That’s what we do in our time off.”

Eastwood smiles. He’s happy that “young Matt” feels the same way he does—loving his work and controlling his destiny. The final words of the poem “Invictus” that inspired Mandela through the years of his imprisonment could be an anthem for each of them:

I am the master of my fate;

I am the captain of my soul.

(COVER STORY/ PARADE MAGAZINE)