It’s rare to find gratitude around the workplace, but appreciation is an even better motivator than money.

By Janice Kaplan

Google’s Larry Page recently got the highest approval ratings of any chief executive on a popular job review site . His likable, low-key style accounts for much of his popularity—but so does his willingness to express gratitude to the people who work for him. The company’s own “Reasons to Work at Google” reflect his way of doing things, declaring: “We love our employees and we want them to know it” and “Appreciation is the best motivation.”

Google and a few other companies are setting a new trend—because expressions of gratitude around the workplace tend to be scarce. In a 2013 survey of 2,000 Americans on gratitude sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation, some 80% agreed that receiving gratitude makes them work harder, but only 10% managed to express gratitude to others every day. “Thanks”—whether sent up, down or sideways—was rarely heard.

Being appreciated is one of the great motivators on the job, even better than money. Researchers at the London School of Economics analyzed more than 50 studies for a 2011 paper that looked at what gets people charged up at work. They concluded that we give our best effort if the work gets us interested and excited, if we feel that it’s providing meaning and purpose, and if others appreciate what we’re doing.

Financial incentives can actually have a negative impact. You need to start with a fair salary, but being given direct payoffs for performance can undermine the intrinsic and personal motivations that make us want to give our all.

Some tough-minded executives worry that gratitude makes them seem less powerful. My friend Beth Schermer, an executive coach and consultant in Phoenix, told me that she tries to encourage managers to show gratitude all the time. “But the comment we hear is, ‘I say thank you to my employees every week. It’s called a paycheck,’ ” she said. She often advises CEOs to start all difficult interactions with “thank you,” because there must be something the person has done right. “It usually makes the conversation go better, even if you’re firing them,” she said.

Adam Grant, a professor of management at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, divides people into three categories—givers, takers, and matchers. Takers try to get other people to serve their needs, and matchers always play a corporate quid pro quo—they will help someone if they think they will get an advantage in return. Givers contribute to others without looking for a reward; they offer help, advice and knowledge, share valuable contacts and make introductions.

In a competitive situation, that readiness to give might seem like it could hold someone back, and sometimes it does. But Dr. Grant found that givers can also end up on top. Those who combine giving to others with an awareness of their own needs can be the most successful on all fronts. They benefit others and advance their own interests, too.

“A sense of appreciation is the single most sustainable motivator at work,” he told me. “Extrinsic motivators can stop having much meaning. Your raise in pay feels like your just due, your bonus gets spent, your new title doesn’t sound so important once you have it. But the sense that other people appreciate what you do sticks with you.”

Dr. Grant and Harvard Business School professor Francesca Gino designed a study in which they asked professionals to advise students about the cover letters they were using to apply for jobs. After receiving the suggestions, the students asked for help with another letter. Some 32% of the professionals agreed. But when students added a single line to their note about the first feedback—“Thank you so much! I am really grateful!”—a full 66% of the advisers agreed to help again. A simple expression of gratitude doubled the response.

A twist on this experiment brought a bigger surprise. After one student had asked an adviser for help, Dr. Grant had a second student do the same. A full 55% of the advisers who had been thanked enthusiastically were willing to help the second student, but just 25% of those who had not. Feeling appreciated doubled their willingness to help others.

So what is the best way to show gratitude at work? The trick is to be specific about what someone has done and to give honest and sincere appreciation. It’s a point that Dale Carnegie made in “How to Win Friends and Influence People,” published in 1936 but still a top seller among self-help books.

A CEO with whom I once worked had taken the Dale Carnegie course, and every week or two, on a Friday afternoon, I’d get an email that said “Dear Janice, Thank you!!!” Sometimes he elaborated to say: “Thank you for all you do!!”

He didn’t quite have down the part about being specific in an expression of thanks, but he was trying—and it meant a lot to me. Any expression of gratitude is better than nothing.

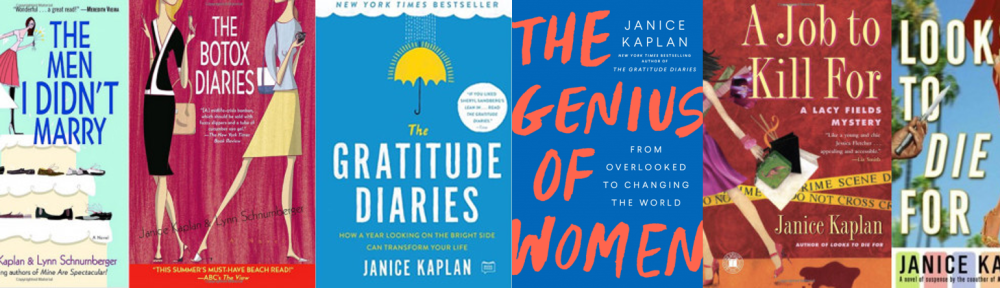

Janice Kaplan is the author of the New York Times bestseller The Gratitude Diaries. Her new book The Genius of Women will be published in early 2020.