Lise Meitner’s co-discovery of nuclear fission in the 1940s led to nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons. But the scientific establishment ignored her ground-breaking work.

The discovery led to the nuclear reactors that generate heat and electricity. And despite Meitner’s antipathy to bomb-making, she paved the way for nuclear weapons. In other words, it was a groundbreaking big deal.

But was she celebrated for it? Not so much.

Meitner collaborated for several decades with a chemist named Otto Hahn, working with him on radioactivity and then fission. They were often talked about for a Nobel Prize and, sure enough, in 1944, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences came through with an award for the “discovery of the fission of heavy atomic nuclei.” But then they announced that the winner was—Otto Hahn.

Not Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner together. Only one half of the team—the male half—got the honor and the recognition and the prize money.

In the early 1990s, some physicists reviewed the proceedings of the Nobel Committee which had just become public and concluded that excluding Meitner was inexcusable. They described it as a mixture of “bias, political obtuseness, ignorance, and haste.” And that was putting it nicely.

Hahn was a great chemist, but he never really understood the theoretical basis of nuclear fission, and he relied on Meitner for the explanations of what was happening. Meitner remained polite after the slight, but as she pointedly explained in a letter about splitting the atom, “how it originates and that it produces so much energy… was something very remote to Hahn.”

The men on the Nobel Committee believed that a woman couldn’t possibly deserve the most prestigious science prize in the world. So even when they had new information—Meitner had made a brilliant discovery!—they dismissed it. A woman could only support a man’s better work. The position might have been built on a hill of sand, but once it became an ingrained belief, it was (and is) tough to knock down.

For Meitner, the bias must have seemed too familiar. Born in Vienna in 1878, she was educated privately until girls were allowed in public universities—and then she got a PhD in physics. With no job prospects for a woman in Vienna, she moved to Berlin. The situation there was a little better, and she became the first woman in Germany to be a full professor of physics.

Hold the cheers, though. Despite her position, she wasn’t allowed into the main laboratories at the University of Berlin and worked out of a carpenter’s shop in the basement. The closest ladies’ room was down the street. Whenever she was walking with Otto Hahn, her colleagues made a point of saying hello only to him. Forget Mean Girls. Mean Boys can be much worse.

When the Nazi regime began closing in, Meitner remained absorbed in her work and didn’t want to leave her lab. Only when Germany began closing its borders in 1938 did she realize that she had to escape. In a touching moment of farewell, Otto Hahn gave Meitner his mother’s diamond ring—not for love but for money. She might need it to bribe the border guards. She ultimately crossed into Holland and then went on to Sweden, where she continued her work. Right under the noses of the men on the Nobel Committee, you might say.

After the war, Meitner continued working in Sweden and never fully addressed the sexism she faced. Maybe she didn’t even see all the obstacles that had been in her way or was too focused on physics to fight the patriarchy, too. We don’t ask genius men to challenge social structures. We just leave them alone to do their work.

After the Nobel Prize snub, she chose to include a colleague in her polite statement that Hahn deserved recognition, “but I believe that Otto Robert Frisch and I contributed something not insignificant…” The Nobel committee never explained its actions and certainly never apologized.

Elements used to be named after mythological creatures or the place they were discovered, but more recent discoveries recognize great scientists like Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr. One is named for Copernicus, who upended our view of the universe by realizing that the earth revolves around the sun. And element 109 on the periodic table is named… Meitnerium.

It’s satisfying to see Lise Meitner, a woman who changed physics with her brilliant insights, nestled nicely with Einstein and Copernicus, her genius enshrined in the periodic table. Let’s not underestimate what a dramatic change that entails.

The scientists honoring Meitner were willing to say that the views men held about women’s roles were simply wrong. They had to upend deeply held (and deeply incorrect) beliefs about gender differences and accept that Lise Meitner was a genius. I have huge admiration for them—and for her.

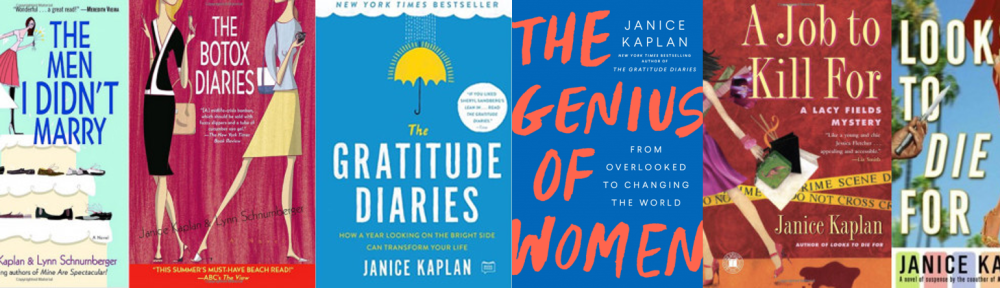

Janice Kaplan is the author of The Genius of Women: From Overlooked to Changing the World, to be published by Dutton on Feb. 18.